This was the title of a fascinating talk by Alec MacKinnon at a recent Probus meeting. If we go to a place where there is a low amount of light pollution we will see stars set in a dark sky. They are of varying intensity, depending on their size and distance away. A pair of binoculars give a more detailed picture. It is possible to see Jupiter’s moons with binoculars.

He started by asking three questions: Is there an edge to the universe? If so what’s outside it? If there’s no edge, then are there stars all the way to infinity?

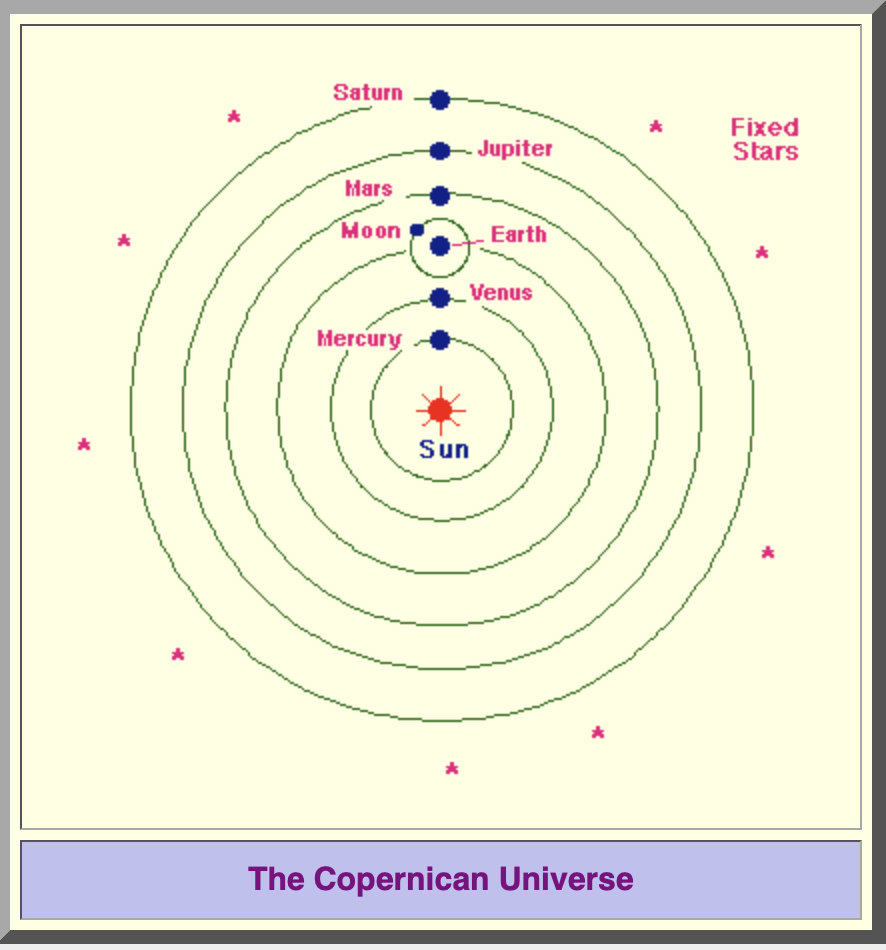

Aristotle’s idea of the universe is with the earth in the centre and planets, including our sun, in fixed orbits around it, finally on the outside a ring of fixed stars.

In the 1500s Copernicus proposed a Heliocentric system, with the sun in the centre, the earth orbiting the sun and the moon in turn orbiting earth; it still had fixed stars:

Galileo then provided observational support for Copernicus’ theory that had been put forward twenty years before Galileo was born. His work was made easier by the use of a telescope. He also observed for the first time that, just like the moon, Venus goes through a full series of phases, waxing from a thin crescent to a full disc and then wanes to a crescent before disappearing before the cycle repeats.

The discoveries of Kepler, another astronomer of the late 16th century turned Copernicus’ Sun-centred system into a dynamic universe, with the Sun actively pushing the planets around in noncircular orbits.

We then ventured into Olber’s Paradox: The paradox is that a static, infinitely old universe with an infinite number of stars distributed in an infinitely large space would be bright rather than dark. We were given a more manageable comparison: If you were in a plantation of trees, you see the nearest ones as individuals then as you look further away, they merge together – a wall of trees. So it would be with the stars, hence the sky should be bright.

Is it that we just don’t see them? The Beehive Cluster of stars is an open cluster in the constellation of Cancer, it’s one of the nearest open clusters to Earth, holding around 1,000 stars. Under dark skies, the Beehive Cluster looks like a small nebulous object to the naked eye, and has been known since ancient times. However, with binoculars or even better a telescope, you can see right through it, to darkness behind.

Similarly with the Milky Way and the Andromeda galaxy, you can see through them. There is no wall of light.

The explanation then got a bit challenging: Is it because there’s dark stuff in between, opaque material? However, if there were, it would surely warm up and then be visible. The universe is expanding though, and its speed of expansion is not what we would expect, due to material we can’t see, because if it can’t emit light, then it can’t absorb light either. Lord Kelvin said in 1901 that the visible universe is very small, whereas the vastness of the universe is inconceivable. Edgar Allan Poe had also noted this in his poem -Eureka – published in 1848.

The only way we can comprehend this is to consider the speed of light. As we look further away, we look further into the past so, in an infinite universe, how far is it before we see a star? The nearest star we can see is Proxima Centauri, 4.2 light-years away (a light year is approximately 5.9 trillion miles). It of course depends upon the size of the star (the sun is a middle-sized star). The Orion nebula is 1,344 light-years away.

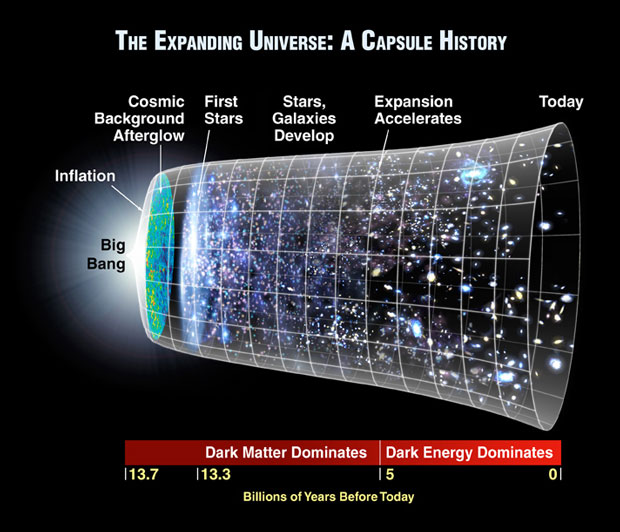

With the universe believed to be 13.8 billion years old, it hasn’t existed for long enough for us to see light from all stars. All galaxies are moving away from the Milky Way, meaning that there is a ’red shift’ in the wave length of the observed radiation, the wavelengths have increased. They have moved out of the visible region of the spectrum into the microwave region.

Many scientists use a visual called the Expansion Funnel to describe how the universe’s expansion has sped up since the Big Bang. Imagine a deep funnel with a wide brim. The left side of the funnel – the narrow end – represents the beginning of the universe. As you move towards the right, you are moving forward in time. The cone widening represents the universe’s expansion. Scientists haven’t been able to directly measure where the energy causing this accelerating expansion comes from. They haven’t been able to detect it or measure it. Because they can’t see or directly measure this type of energy, they call it dark energy.

According to researchers’ models, dark energy must be the most common form of energy in the universe, making up about 68% of the total energy in the universe. The energy from everyday matter, which makes up the Earth, the Sun, and everything we can see, accounts for only about 5% of all energy. There is also dark matter.

There is a cosmic microwave background radiation, if you are tuning a radio, you hear a ‘hiss’ between stations, this is the background sky ‘glow’. The book Darkness at Night by E R Harrison goes a long way towards answering the question.

“The answer to this ancient and celebrated riddle, says Edward Harrison, seems relatively simple: the sun has set and is now shining on the other side of the earth. But suppose we were space travellers and far from any star. Out in the depths of space the heavens would be dark, even darker than the sky seen from the earth on cloudless and moonless nights. For more than four centuries, astronomers and other investigators have pondered the enigma of a dark sky and proposed many provocative but incorrect answers. Darkness at Night eloquently describes the misleading trails of inquiry and strange ideas that have abounded in the quest for a solution.”

The universe has not always existed and stars do not shine for ever. If we had microwave sensitive eyes, we would see that the universe is uniformly illuminated, by radiation from before stars existed. The darkness between stars is visible evidence for the exotic stories of astrophysics and cosmology.

A reminder of Alec’s three questions, I’ve tried to answer them:

Is there an edge to the universe? Astronomers are unsure, we can’t see it, perhaps it’s really the edge of time.

If so what’s outside it? Astronomers don’t know, there are a number of suggestions: an Infinite Universe, a Finite universe, a Cosmic Void and other dimensions or universes.

If there’s no edge, then are there stars all the way to infinity? We don’t know!

If you are interested then start looking on the web. I think I’ll need to buy a copy of Harrison’s book!

Why not join us at our next meeting?

New members are always welcomed at the Club. If you are 50 or over, retired, or nearing retirement, (men only, I’m afraid, sorry ladies) you can attend three meetings as a guest and find out what a relaxed and friendly time we have. That’s plenty of time to decide whether to become a Club member or not. Please check out our programme and email info@largsprobus.org.uk if you wish to attend as a guest, or to enquire about joining.

Largs Probus Club will next meet in the Willowbank Hotel on Wednesday 4th February at 10am when Fraser Sutherland will give a talk on Humanism.