At a recent meeting of Largs Probus Club, astrophysicist and adult educator Alec MacKinnon spoke to us on the topic of Physics and Ben Nevis. He is currently Honorary Research Fellow in the School of Physics and Astronomy, University of Glasgow. The starting point for developing his talk was his feeling that Scotland should celebrate its notable scientists just as much as it does its musicians, writers, artists… CTR Wilson was Scotland’s first Physics Nobel Prize winner, in 1927, and there wasn’t another one until 2016. But his name doesn’t seem as well-known as it should be. So, it was time to give some biography of Wilson and talk about what he actually did.

Wilson’s story is firmly rooted in Scotland, involving locations that many people know and love, and crossing paths with the heroic tales of the Ben Nevis Observatory. It’s also quite a circuitous story, involving several accidents of place and personality. So, it gives an accessible, human way of discussing some ideas from particle physics and cosmic rays. He himself, in the first sentence of his Nobel acceptance speech, drew a direct line from his time on Ben Nevis to his invention and development of the cloud chamber.

CTR, as he was known, was born in February, 1869, in the parish of Glencorse, near Edinburgh. Having been educated in Manchester, he went to Cambridge, initially to study medicine, but he became interested in the physical sciences, especially physics and chemistry, he took his degree in 1892.

The word ‘observatory’ usually makes people think of astronomy but the Ben Nevis Observatory was for meteorology and CTR’s two weeks as a volunteer observer at the Ben Nevis Observatory in 1894 proved highly influential. Ben Nevis Observatory had opened in 1883 after political pressure, careful planning and with an enthusiastic observer, Clement Wragge, climbing the mountain daily in summer 1881 to take observations and argue for their continuation. By the time of CTR’s visit, the observatory was well-established with a superintendent; the staff of three made hourly observations in all but the most extreme conditions during those years (It closed in 1904, due to lack of adequate funding.) The mountain’s climatology included regular hill fog, present 88% of the time in December and January, dropping to a modest 53% in June.

Optical phenomena such as coronae, haloes and glories were common at Ben Nevis, and CTR’s visit took place during the driest month in its history, when rainfall was only 8% of average, with an unusually prevalent northerly and easterly flow. The temperature inversions would have been ideal for glories, described in detail by all the observers. CTR was employed as vacation relief for one of the permanent staff for a couple of weeks in September 1894. While he was there his scientific curiosity was captured by sightings of these glories, Brocken Spectre, an optical phenomenon that occurs when rays of light are reflected back from water droplets in almost the direction they came from. It occurs in a way that’s related to the rainbow but the detailed explanation is more complex. It wasn’t really understood in Wilson’s time.

Back in Cambridge he started doing experiments to try to understand the Brocken Spectre, constructing a device in which little clouds of water vapour could be produced. However, he began to realise that water droplets, under conditions of very low pressure, started to form on ions (charged particles). An energetic electron or ion leaves a trail of ions as it passes through air and these can all become sites for the formation of water droplets, so, in the cloud chamber, the paths of these subatomic particles are made visible.

He started out thinking about meteorological optics but came across something more fundamental. He commented later on how important it was to have been doing his work in Cambridge just as they were starting to unravel the physics of atoms and ions, X-rays, and “radiation” – another happy accident of place.

The invention of the cloud chamber was by far CTR’s most important accomplishment, which earned him the Nobel Prize for Physics in 1927. The Cavendish laboratory praised him for the creation of “a novel and striking method of investigating the properties of ionized gases”. The cloud chamber allowed huge experimental leaps forward in the study of subatomic particles and the field of particle physics, generally. Some have credited Wilson with making the study of particles possible at all

Our speaker also spoke a little about radiation from the rest of the cosmos. Wilson suspected some such radiation might be responsible for the ionisation of air at sea level so he did an experiment to test this idea in the tunnel of the Caledonian Railway near Peebles. This seemed to rule out such cosmic radiation but it wasn’t really the right experiment. Cosmic rays, as they’re called, were decisively detected in a balloon-borne experiment in 1911 but Wilson gets the credit for suggesting the possibility and for carrying out what was probably the first cosmic ray experiment. Most cosmic ray PhD theses – in the UK at least – start from Wilson on Ben Nevis.

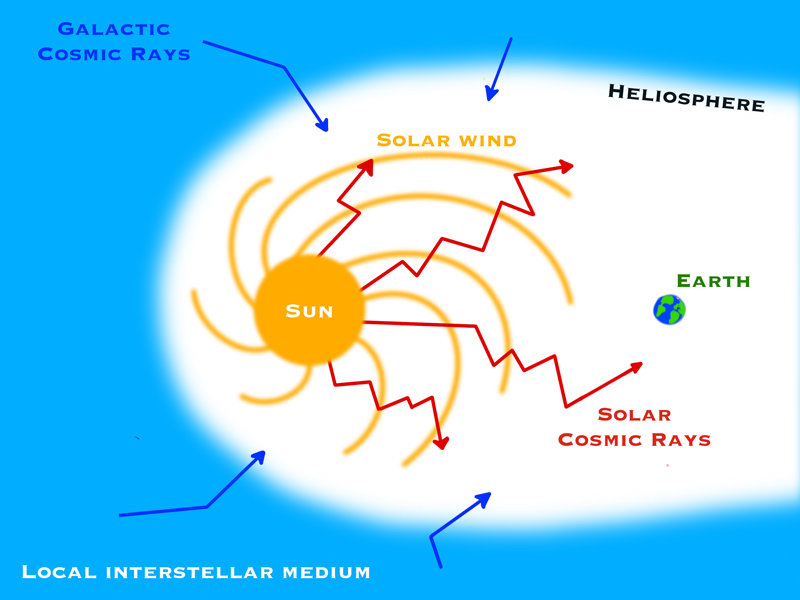

Our speaker didn’t mention at the time, but has in a recent communication, clarifying the writing of this post; that this is really where the connection to his own work comes. Alec is interested in energy release and particle acceleration at the Sun, in the events of solar flares and associated phenomena. If energetic particles interact with the solar atmosphere, they produce X-rays and gamma-rays but if they arrive at Earth, they’re ‘solar cosmic rays’. He went on to say that the steadier component of cosmic rays, so-called “galactic cosmic rays” come from the Milky Way more broadly, having been accelerated in the blast waves that follow supernovae, the explosions that end the lives of stars much more massive than the Sun.

I assume that our speaker will have been very interested in the NASA’s Parker Solar Probe making history with the closest pass to the sun yet made.

For anyone who is scientifically minded, yes, I’ve read it, this article is of interest as it defines solar and galactic cosmic rays. And here’s a diagram to help, from Taking Stock of Cosmic Rays in the Solar System.

Why not join us?

New members are always welcomed at the Club. If you are 50 or over, retired, or nearing retirement, (men only, I’m afraid, sorry ladies) you can attend three meetings as a guest and find out what a relaxed and friendly time we have. That’s plenty of time to decide whether to become a Club member or not. Please check out our programme and email info@largsprobus.org.uk if you wish to attend as a guest, or to enquire about joining.

Largs Probus Club will next meet on Wednesday 30th April at 10:00am within the Willowbank Hotel, when Sandra Savona will speak on Home Instead.